Next: Displaying STAMP output (VER2HOR,

Up: A brief description of

Previous: Multiple alignment (TREEWISE)

Contents

It is often desirable to compare a particular domain or protein

structure to a database of known 3D structures in order that structurally similar

proteins may be found.

Given a single protein domain (a query) and a list of domains to which it is

to be compared (a database), STAMP can be used to perform all possible

comparisons of the query to the database structures. The initial

superimposition problem is solved by attempting more than one

initial fit with each database structure. This can be done in one of two ways,

which are named FAST and SLOW, for the obvious reasons.

In FAST mode, fits are performed by laying

query sequence onto the database structure starting at every  th position,

where

th position,

where  is an adjustable parameter usually set to five (i.e. the sequence

is laid onto the 1st, 6th, 11th, etc. position). Diagramatically, this looks

like:

is an adjustable parameter usually set to five (i.e. the sequence

is laid onto the 1st, 6th, 11th, etc. position). Diagramatically, this looks

like:

Q=query, D=database

Fit 1 Q -------

D -----------

Fit 2 Q -------

D -----------

Fit 3 Q -------

D -----------

<etc.>

This approach is fine if the query is a single domain, and there is a strong similarity in

the database structure. However, if similarity is weaker, or if the query contains multiple domains (

in which case it is advisable to split the query into multiple domains, if possible), then SLOW mode will perform more fits by sliding query and database sequences along each other like:

Q=query, D=database

Fit 1 Q -------

D -----------

Fit 2 Q -------

D -----------

Fit 3 Q -------

D -----------

<etc.>

Fit N-2 Q -------

D -----------

Fit N-1 Q -------

D -----------

Fit N Q -------

D -----------

In this approach, initial superimpositions are calulated using many more fractions of query and

database structure, making detection of weak similarities more likely.

The residues that are

equivalenced by either FAST or SLOW procedures are used to perform an initial fit, which is

refined by the conformation-based and distance-based fit used during

PAIRWISE/TREEWISE comparison of distantly related structures. If a

high enough similarity score ( ) is found after these three

steps, then the transformation is saved for further analysis.

The output from SCAN mode is directly readable by STAMP so

that once a list of domains similar to one's query is obtained,

multiple alignment (ie. PAIRWISE and TREEWISE) can be performed.

) is found after these three

steps, then the transformation is saved for further analysis.

The output from SCAN mode is directly readable by STAMP so

that once a list of domains similar to one's query is obtained,

multiple alignment (ie. PAIRWISE and TREEWISE) can be performed.

The program PDBC can be used to generate a list of protein domains

given a set of PDB identifier codes, and the program SORTTRANS can

be used to sort the output from SCAN, and remove any redundancies.

The Sc values output in SCAN mode differ slightly from those

output during a PAIRWISE comparison. The correction introduced

to correct the SW Score according to the length of the sequence

lengths is removed. During multiple alignment the start and end

points of the domains to be superimposed should be known; thus one

can penalise all positions which are not involved in the

alignment. During a scan, however, it is desirable to detect sub

alignments of the two structures being compared

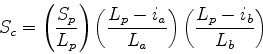

Thus, the Sc for scanning may be defined in one of

three ways (a=query, b=database, p=path, i=insertion, L=length):

Scheme 1

As for multiple structure alignment. As discussed, this is generally not the

best way to compare a

query to the database, since one would not usually wish to penalise insertions

or omitted missing segments within the database structure (due to truncation values,

etc.). However, this scheme may be useful if one is scanning a database of

structures known to exhibit a particular fold (i.e., if one is merely after

accurate superimpositions for a family of known structures; see Chapter 2).

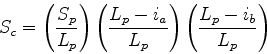

Scheme 2

and

and  have been replaced by

have been replaced by  to removed any dependence

on query or database structure length. The second two terms

lower the score if gaps in the path are placed in the query (a) or

database structure (b). This avoids a consideration of length, but will

allow short stretches of structural equivalences to score highly.

to removed any dependence

on query or database structure length. The second two terms

lower the score if gaps in the path are placed in the query (a) or

database structure (b). This avoids a consideration of length, but will

allow short stretches of structural equivalences to score highly.

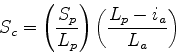

Scheme 3

Only penalises insertions in the query sequence. If a small

fraction of the query sequence is in the actual path, then

drops.

This scheme is most useful if one wants only similarities

to the entire protein under consideration, since it penalises

any omissions from the query structure.

drops.

This scheme is most useful if one wants only similarities

to the entire protein under consideration, since it penalises

any omissions from the query structure.

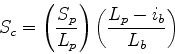

Scheme 4

The opposite of 3. Only penalises insertions in the database sequence.

If a small fraction of the database sequence is in the actual path, then  drops. This scheme may be useful if one is scanning with a collection of

secondary structure elements, since gaps are to be expected within the

query (i.e. since the loops have been omitted).

drops. This scheme may be useful if one is scanning with a collection of

secondary structure elements, since gaps are to be expected within the

query (i.e. since the loops have been omitted).

Scheme 5

Raw score, no length requirement, will report even short alignments between

similar sub-structures. This scheme may be useful for the search for

short stretches of structural similarity, such as supersecondary structures.

Scheme 6

Vaguely similar to Scheme 3, but this only scores hits favourably

if they involve a significant fraction of the query structure

(i.e. similarities only containing part of the query will not

stand out). This is useful when one is comparing a particular

domain to a database and is not interested in local similarities.

This is the default for scanning.

For the most part, all of these scoring schemes will yield similar

numbers for very similar structures. However, when more distantly

related structures are compared, it becomes more useful to use a

scheme specific to the particular problem (i.e., whether one wishes

to scan with secondary structures only, when one is after only

very similar structures, etc.).

Schemes are specified by the STAMP parameter SCANSCORE (see below). If

you're not sure which scoring scheme to use then you should just

use the default scheme.

Next: Displaying STAMP output (VER2HOR,

Up: A brief description of

Previous: Multiple alignment (TREEWISE)

Contents